A Miami Law Student Wants a ‘Student Bill of Rights.’ Really? By Elie Mystal Usually I’m happy to stand with law students against the slings and arrows of outrageous law school administration.

But not this time. This time, instead of a noble law student fighting the good fight, I see an annoying whiner who wants law school to be about teddy bears and rainbows.

A student at the University of Miami School of Law is trying to get the student body to adopt a “Student Bill of Rights.” The proposal lists a number of things that “shall not be violated.” Even though I agree with some of these points, codifying them as “rights” makes me flaccid. We’re talking about law school, not summer camp. It’s supposed to be hard. It’s not supposed to be fair. We can condemn law schools until the cows come home for inducing students to sign up under false pretenses. But once you matriculate, law schools turn into the warden from Shawshank Redemption: “Put your trust in the Lord; your ass belongs to me.” As a law student, you don’t have any rights…. Even the set-up for this “Bill of Rights” is vomitous. Listening to this kid wax poetic about “students’ rights” is like watching LeBron James take an hour to tell us where he’s going to play basketball. And like LeBron, I kind of wish this kid would “take his talents” and shove them right back up his ass: Over winter break [Redacted], a 2L here at UM law, came to me with a proposition — a proposition to reform the law school experience. You see, [Redacted] has been very dissatisfied with her legal education. She believes that the majority of her frustration comes from the fact that professors have a great deal of power over their students and students are not given much leverage in which to counteract that power, which leads professors to abuse their power which consequently produces an unpleasing classroom experience for students. In order to remedy this situation, [Redacted] sought of a way to empower students in the classroom in order to counteract/keep-in-check professor behavior. Hence, the Student Bill of Rights was born. The Student Bill of Rights seeks to codify all legitimate concerns that students have involving their legal education. Once codified, these rights will be engrained [sic] into the legal education system, which will help raise awareness to professors that they must protect these rights and to students that they have the right to have these concerns respected. This will help establish equilibrium between professor and student rights, which will lead to a more enjoyable classroom experience for law students. While we understand that nothing will change over night we are eager to see the groundwork for a culture change to occur…. The student body will vote on the Student Bill of Rights in this month’s SBA election. It will be attached to the ballot as a referendum that hopefully will be added to the SBA Constitution and the Student Handbook. Really? Really dude? You’re going to reform the law school experience? From Miami Law School? With a document? Why don’t you try reforming your dating life, since you clearly have too much time on your hands? Really. I mean really, you just said that students don’t have much leverage. So how does making a bill of rights really give them any more leverage? Because it’s been “codified” by other law students? Sounds like somebody doesn’t understand the concept of “enforcement powers.” You really misspelled the word “ingrained.” Really? I make typos like I get paid for them (and I kinda do), and even I wouldn’t make that kind of an error. Really, don’t try to bite my style, it’s harder than it looks. I mean, “ingrained” wasn’t even the word you were looking for in that sentence. No, really. You wanted to say something like “adopted” or “accepted” or “acknowledged,” and that’s just using words starting with the first letter of the alphabet. I really believe that there are at least three words per vowel that would make more sense there. And I really don’t know who told you that the classroom experience was supposed to be “enjoyable,” but that person owes you money. Really. Really, dude. If class was supposed to be fun, they wouldn’t call it “class.” If you don’t like class so much, why don’t you just read Above the Law during class, like the rest of your friends? Really. You don’t need a bill of rights, you need a wireless internet connection. I mean really, what is wrong with you? Really? Miami Law students, if you vote for this thing I’ll shoot you on general principle. CORRECTION: The version of the email I received did not reveal the gender of the person championing the Bill of Rights. I assumed it was a guy because it reeked of the bravado inspired by a Y-chromosome. Turns out the “he” is a she. Really. I apologize for the error.

1. I am underpaid for what I do: Cornell University Prelaw Program in New York City June 6-July 15, 2011 Program description: If you're thinking about becoming a lawyer—or simply want to know more about the law and how it affects our everyday lives—you're invited to be a part of the Cornell University Prelaw Program. This intensive, six-week program taught in New York City is directed by C. Evan Stewart, one of America's most distinguished lawyers. Program features - a four-credit course, "Introduction to the American Legal System," taught using the Socratic method used at most U.S. law schools;

- a limited number of selective internship placements at law firms or in the legal department of a corporation, government agency, or nonprofit organization; and

- the opportunity to explore the law and culture of New York City.

Program structure During the first three weeks of this rigorous program, you meet with Professor Stewart for class each morning. Classes are held at Pace University, located in the heart of the financial district. During the second three weeks of the program, if you've received a placement, you devote full days to your internship. (Note: The program dates for students who either do not receive a placement or opt not to participate in an internship are June 6-24.) The program is designed for undergraduates who will complete their sophomore year or higher by June 2011, and for college graduates who wish to gain an accurate, comprehensive understanding of America's legal system. Because of the intensive and individualized nature of the program, enrollment is strictly limited. If you're considering applying, we urge you to do so as early as possible. Program benefits Through the Cornell University Prelaw Program, you have an unparalleled chance to develop an accurate picture of the realities, rewards, and challenges of being a lawyer today. Throughout the program, you'll address such questions as: - How do the careers of lawyers portrayed in Boston Legal and Law & Order compare to those of real-life lawyers?

- How much of my legal career will involve arguing over lofty Constitutional issues?

- Will my success as a lawyer hinge on being the smartest person in the room?

- Will I make a lot of money if I go to law school and become a lawyer?

- What's so great about being a lawyer?

You'll also have the opportunity to: - explore the varieties of professional roles open to lawyers before you invest time, effort, and money in law school;

- prepare for law school, other professions, or a lifetime of informed citizenship;

- gain a comprehensive grounding in fundamental legal concepts and techniques;

- learn firsthand the ins and outs of the legal system from a top attorney;

- develop professional contacts; and

- enhance your academic record, resumé, and skills.

2. Your tuition here is too low:Program Charge The total program charge is $4,970. This includes tuition of $4,220 and a nonrefundable program fee of $750. Text book purchases are to be made by the students. Housing and meals are not included. You're responsible for finding your own housing; a variety of housing options are available. Upon acceptance to the program, the full program charge of $4,970 becomes due.

Karen Sloan

February 10, 2011

Associates at Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy are heading to Harvard.

The firm has agreed with Harvard Law School to launch what it believes is a first-of-its-kind associate development program. Mid-level associates will attend annual eight-day training sessions focused on business principles at the Cambridge, Mass., campus.

The program is called Milbank@Harvard.

It's not uncommon for law firms to send attorneys through intensive executive training courses at top academies such as the Wharton School and the University of Pennsylvania, but those programs often are geared toward leadership development for partners. Milbank's program will be open to all third- through seventh-year associates.

"We don't know of anyone who is doing something like this," said Milbank Vice Chairman Scott Edelman. "For one thing, it's going to involve every associate in the firm and a commitment over a period of years. It's not a one-year program."

Law firms have been moving away from affiliations with prestigious academic institutions, said Eric Seeger, a consultant with Altman Weil who specializes in law firm strategy. Firms are serious about instilling the skills they want associates to have, but most of those efforts are being handled internally, he said.

"It's good branding to be associated with Harvard. That has some value," Seeger said. "It might also have some recruiting and retention benefits."

Larry Richard, a consultant who runs the leadership and organization development group at Hildebrandt Baker Robbins, hasn't seen anything quite like Milbank@Harvard. There is a reason that most firms don't send mid-level associates off for business training, he said. Attorneys tend to be more receptive and motivated to learn new things early in their careers, and research shows that educational efforts are most effective when students are interested in their subject matter.

"They're talking about teaching things like economics and finance," Richard said. "Will every lawyer be interested in that? I don't know."

Still, sending associates to learn about business and client relations can't hurt, Richard said. The team atmosphere that results from bringing together associates from all offices may well prove the biggest benefit. "There is an indispensable role that face-to-face contact has in building connections," Richard said.

Team building indeed is one of Milbank's goals, Edelman said. So is increasing associates' investment in the firm. Some 40 associates will go though the program at a time, with 100 to 150 completing the training annually. Another goal is to turn associates into savvy businesspeople who understand what's important to clients, he said.

Faculty members from Harvard's law and business schools will teach the sessions, and Milbank partners will be involved. The program is being developed by the firm and Harvard law professor Ashish Nanda, executive director of the school's executive education program. Nanda in 2008 helped Linklaters develop the Linklaters Law and Business School, an extensive professional development program.

Learning about business principles in a Harvard classroom still won't be as effective as secondments with clients, which show associates how the client's business really functions, Richards said.

And including every associate may not be the best way to meet the individual needs of either attorneys or clients, Seeger said. "It surprised me that they will put all their associates through the program," he said. "Our experience is that a one-size-fits all experience is not the most efficient."

Perhaps another surprising element is the financial investment the program represents for Milbank. It includes not only the cost of the program but the time associates will spend away from client matters.

That was a significant consideration for Milbank, Edelman said, but the firm already holds four five-day conferences for associates during their first seven years with the firm.

Law firms have been rolling back spending on attorney development, according to a 2010 survey by the National Association for Law Placement. More than half of the survey respondents reported that their firm's professional development budgets decreased by 10% or more between 2008 and 2010.

Milbank associates are embracing the program, Edelman said. "Associates are really charged up about it and excited about doing it."

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLORADO

Civil Action No. 09-cv-00894-JLK

CONNIE PERRY,

KENT MENGE,

CHUCK WEDDEL,

Plaintiffs,

v.

AT&T OPERATIONS, INC.,

Defendant.

________________________________________________________________________

ORDER STRIKING MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT

AND RELATED BRIEFING

________________________________________________________________________

KANE, J.

This overtime compensation action is before me on Plaintiffs Motion for Summary

Judgment (Doc. 47). Plaintiffs contend they were non-exempt employees who regularly

worked more than 40 hours a week and were not compensated for their overtime hours in

violation of the § 207(a)(1) of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FSLA) and Colorado Wage

Order 24, Colo. Code Regs. § 1103-1. Plaintiffs submit affidavits attesting to the fact that

they were “forced” to work more than 40 hours per week and that they were not

compensated for their excess hours, and argue that Defendant’s failure to keep adequate

records of the hours worked by employees precludes its ability to rebut Plaintiffs’

evidence and entitled them to judgment as a matter of law. I have spent considerable time

with the parties’ briefs and disagree.

In both form and substance, Plaintiffs’ summary judgment theory of relief and

their briefing are inadequate. Plaintiffs characterize both their Fair Labor Standards Act

(FLSA) and state law wage claims in only the most general terms,1 support those claims

with legal conclusions, non sequiturs, and minimal and unpersuasive legal authority,2 and

pepper their briefs with miscitations and grammatical errors.3 Most importantly,

a wage claim plaintiff based on reasonable estimates of uncompensated overtime hours even

when an employer presents sworn testimony in rebuttal. To the contrary, the trial court in Doty

ruled for plaintiffs only after a trial on the merits where the court, as the trier of fact, weighed the

evidence, as I am specifically precluded from doing on summary judgment. If anything, Doty

supports a denial of Plaintiffs’ motion, so that the parties’ competing evidence may be weighed

by the trier of fact.

1 In their Complaint (Doc. 1), Scheduling Order (Doc. 19), and summary judgment

briefing, Plaintiffs claim Defendant has violated their rights under “29 U.S.C. § 201, et seq.,”

the elements of which Plaintiffs contend are set forth at 29 U.S.C. § 207(a) (1) and “29

U.S.C. § 785.12 (1997).” Mot. Summ. J. (Doc. 47) at 9-10. FLSA Section 207(a) is the

Act’s general prohibition that “no employer shall employ any of his employees . . . for a

workweek longer than forty hours unless such employee receives compensation for his

employment in excess of the hours above specified at a rate not less than one and one-half

times the regular rate at which he is employed.” After some consternation I realized the

citation to “29 U.S.C. § 785.12 (1997)” was likely a citation to a thirteen-year-old version of

29 C.F.R. § 785.12, which provides that employers must pay overtime for work “performed

away from the premises or the job site,” a subject about which Plaintiffs argue elsewhere in their

briefing but not in the section of page 10 of their opening brief where the regulation is cited.

2 In their reply in support of the undisputed facts they averred in their opening

brief, for example, Plaintiffs respond to Defendant’s denial that AT&T managers ever emailed or

“quequed” with Plaintiffs after hours by asserting “whether or not Plaintiffs corresponded with

their managers via queque [or email] after hours, AT&T was still on constructive notice that

Plaintiffs were working overtime hours.” Reply Br. at p. 6, ¶¶ 16-17 (Doc. 58)(emphasis mine.)

Not only does the conclusion not follow from the premise, but it is a legal one insufficient to

support a claim even under a Rule 12(b)(6) standard, let alone the standard governing motions

for summary judgment under Rule 56. See Bell Atlantic Corp. v. Twombly, 550 U.S. 544, 555

(2007), applied in Ashcroft v. Iqbal, 129 S.Ct. 1937 (2009).

3 In arguing their entitlement to summary judgment, for example, Plaintiffs cite

Doty v. Elias, 733 F.2d 720, 725 (10th Cir. 1984), for the proposition that “Courts have been very

differential [sic] to employees when examining evidence that employer’s [sic] try to use to

negate the employee’s reasonable estimate of uncompensated overtime hours.” Pls.’ Mot.

Summ. J. (Doc. 47) at 17. Besides the inclusion of distracting grammatical/typographical errors,

the case Plaintiffs cite in no way supports the proposition they purport to make, namely, that

district courts have in the past, or that this court should, in this case, grant summary judgment to

It is not the time-consuming burden of this court to proofread and correct errors, or, in the

case of the miscitation of 29 U.S.C. § 785.12, to determine what the correct citation was

intended, simply to understand what represented parties are trying to communicate in their

briefs.

Plaintiffs’ briefs read like trial briefs full of argument on disputed points of fact.

Plaintiffs contend, for example, that they have “proven” each of the elements of a wage

act claim, asserting AT&T managers had “actual knowledge” that Plaintiffs were working

overtime and maintaining those managers’ sworn affidavits to the contrary “are not

credible.” Mot. Summ. J. (Doc. 47) at 9; Pls’ Reply at 15. This is not the stuff of

summary judgment, it is the antithesis of it.

The essence of Plaintiffs’ argument on summary judgment is that the Department

of Labor has already investigated AT&T and issued a report finding AT&T to have

maintained, for a period of time that has since expired, inadequate records of employee

hours worked and that two of the three Plaintiffs were owed overtime compensation for

work performed from the date they were hired in April 2007 to September 2007, and that

these findings somehow relieve Plaintiffs of any burden on summary judgment other than

to present evidence from which the existence and number of additional overtime

violations since can be inferred. This is incorrect.

Under old, but apparently still applicable Supreme Court precedent, where an

employer in a wage act case has kept inaccurate or inadequate records, “an employee has

carried out his burden [of making out a claim for unpaid minimum or overtime wages

under the Act] if he proves that he has in fact performed work for which he was

improperly compensated and if he produces sufficient evidence to show the amount and

extent of that work as a matter of just and reasonable inference.” Anderson v. Mt.

Clemens Pottery Co., 328 U.S. 680, 687 (1946). If this burden is met, however, “the

burden then shifts to the employer to come forward with evidence of the precise amount

of work performed or with evidence to negative [sic] the reasonableness of the inference

to be drawn from the employee’s evidence.” Id. at 687-88. On the record before me,

Plaintiffs’ initial burden is the subject of strenuous objection and denial in sworn

affidavits by the managers charged with supervising them and overseeing their work, and

those same managers offer emphatic, and emphatically disputed, testimony to support

their burden of negating the reasonableness of the inference to which Plaintiffs claim they

are entitled. It is, in short, completely unreasonable to conclude in this case that a

reasonable trier of fact could find only in favor of Plaintiffs on their claims. Under these

circumstances, Plaintiffs’ Motion for Summary Judgment would be subject to denial on

the merits even if I were to consider the briefing as filed. See Robertson v. Board of

County Comm’rs, 78 F. Supp.2d 1142, 1160 (D. Colo. 1999)(Babcock, J.)(finding in

favor of wage claim plaintiffs in part after weighing evidence on the merits), aff’d, 166

F.3d 1222 (10th Cir. 1999)(unpublished).

Before concluding, I pause also to reflect on Defendant’s submissions.

Defendant’s submissions constitute an effort to rebut Plaintiffs’ allegations regarding

overtime compensation due and their managers’ awareness that (1) those hours were, in

fact, worked, and (2) that Defendant avoided having to compensate Plaintiffs for them by

creating an atmosphere where employees felt claiming overtime would reflect poorly on

their performance and job security and therefore did not request or seek approval for

overtime compensation. Because they are sworn statements essentially denying and

completely recasting almost every fact alleged, it is hard to arrive at a conclusion other

than that someone or other is perjuring him or herself under oath. Defendant is

admonished that should any of the testimony it has proffered to rebut Plaintiffs’ Motion is

ultimately be shown to have been false when made, not only Defendant but also the

individual witnesses/affiants and Defendant’s counsel, may each be subjected to sanctions

to and including a referral to the United States Attorney. The same holds true for

Plaintiffs and Plaintiffs’ counsel.

Based on the foregoing, the Motion for Summary Judgment and briefs in support

and in opposition thereto are STRICKEN with leave to refile. If Plaintiff chooses to refile

its Motion, it should do so on or before January 13, 2011. Defendant’s refiled Response

shall be due on or before January 21, 2011, and any Reply shall be due on or before

January 28, 2011. The Court is aware that Magistrate Judge Shaffer has set this case for a

Final Pretrial Conference on February 1, 2011. The parties are strongly encouraged to

confer on the issue of settlement before the Pretrial Conference date and to let Magistrate

Judge Shaffer know whether further settlement negotiations would be helpful. I express

no view on the advisability of settlement one way or the other, but it does appear that the

case is one that must be tried, to whatever assessable risk to the parties as such a trial may

portend.

Dated January 6, 2011.

s/John L. Kane

SENIOR U.S. DISTRICT JUDGE

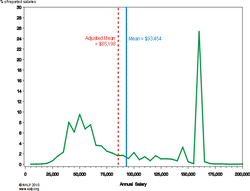

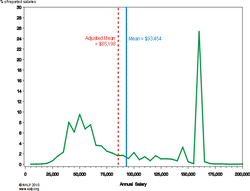

This is the salary range for 2009 law school graduates entering full time law positions.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed